“Hi. I got a tape I wanna play.” With this dry but oh so legendary opening line, the concert film Stop Making Sense by the new-wave band Talking Heads begins. 2023 marks the 40th anniversary of the release of Stop Making Sense. Starting January 11, 2024, the concert film will once again be shown in Dutch cinemas and abroad.

The words come from the mouth of David Byrne. You don’t see him yet. Only the white sneakers on an empty stage. The floor is plastered with white marker strips. A hand clicks on a ghetto blaster and you hear a beat from a cassette tape.

It is the start of the best concert film of all time. The film soon receives the 1984 Best Documentary award from America’s National Society of Film Critics. At the fourteenth 1985 Rotterdam Film Festival, the film is most appreciated, as the emotions splash off the screen. Stop Making Sense puts music films like The Last Waltz far in the shade.

Talking Heads

Talking Heads starts out as the three-man formation of dropouts from art school in the mid-’70s. Before that, Chris Frantz and David Byrne perform as The Autistics (sometimes also Artistics). When performing, Byrne shaves off his beard to the point of blood. Tina Weymouth comes to play bass and Jerry Harrison joins after The Modern Lovers break up. After Brian Eno as producer enhances the band musically immensely by adding samples and African polyrhythms and soundscapes, the band also grows in personnel size. Then you immediately catch the film’s thread on the first layer: the development of Talking Heads up to the 1983 tour and subsequent album Speaking in Tongues.

The band is characterized by intelligent lyrics about self-development, nihilism and human relationships. They bring art to pop music by experimenting with hybrid forms: music and religions from other cultures, modern dance and modern media culture. They are borderless, incorporating rock, pop, country, funk and African and Brazilian music into their music. Four albums end up on a list of most influential records. Three songs by Talking Heads are inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame of 500 songs that have shaped rock music. The band is listed in the top 100 most important musicians of all time.

When film director Jonathan Demme sees Talking Heads in concert in 1983, he is excited about the cinematic possibilities. Byrne later contacts Demme with a proposal to turn the concert into a documentary. The idea of the film is to give a cinema audience the best possible experience of the concert as such. They agree on a budget of $1.2 million, and Stop Making Sense is shot in December 1983 during a series of four specially designed and lit concerts at the Pantages Theater in Hollywood. It premieres April 24, 1984 at the San Francisco International Film Festival.

Foreland of Stop Making Sense

In the early 1980s, David Byrne became increasingly interested in performance theater. He applies the working methods that work in theater to the band’s live concerts. That combination of pop music and theater brings Talking Heads’ greatest fame, both on stage but even more so in innovative music videos and concert film. Byrne is aware that media culture and pop music are a fantastic mix. (It is therefore no coincidence that the videos of Once in a lifetime, Slippery people and Road to Nowhere provide their biggest hits.)

An important angle for the film is Byrne’s collaboration with theater director Robert (“Bob”) Wilson. In parallel with the production of Stop Making Sense was his enormously ambitious 12-hour-long project, The CIVIL WarS: : A Tree is Best Measured When It Is Down. The opera was to be performed during the 1984 L.A. Olympics. It was also planned to be performed in several locations, including Rotterdam and Paris. This did not happen because of logistical problems. The music is by Philip Glass, David Byrne and Gavin Bryars. Later, in 1985, Music for the Knee Plays does come out as an album as a small part of the music opera and a live performance was broadcast by the BBC.

David Byrne then had been following Wilson’s work for some time. Wilson’s Einstein on the Beach (1976) with music by Philip Glass had impressed him for its deliberate slowing of time and the sense of a setting without plot. Wilson separates visual elements from text and music and has his own take on lighting and props.

Byrne is influenced by Bob Wilson. For example, he writes the music score for The Catherine Wheel from September 1981, a dance production on Broadway by Twyla Tharp.

David Byrne uses some elements of this “Wilson doctrine” in the Speaking in Tongues tour, which serves as the basis for the film. Each song is approached as a separate small play; each with its design and lighting.

The Speaking in Tongues tour could not be done with four band members. Two groundbreaking records were released in 1980 and 1981: Remain in Light and My life in the bush of ghosts. In his book How Music Works, David Byrne he explains how they grew from studio record to live concert. “Brian Eno and I had just finished our own LP My Life in the bush of ghosts together. That used the same technique that we would use for Remain in Light shortly thereafter, although in this case neither of us wrote or sang the lyrics, which were all from found sources. We couldn’t play the the “sampled” vocals live. A live performance was really a different story. In addition to Adrian (Belew), we added Steve Scales on percussion, Bernie Worrell on keyboards, Busta Jones on second bass guitar and Dolette McDonald’s as vocalist. Rehearsals were chaotic at first. I especially remember that Jerry was very good at deciding who would play what. Of course, what finally came out didn’t sound exactly like it did on the record. It became more and more funky, the fun over the groove became more apparent.”

Shooting and editing

Distractions are avoided in the film. No dressing room interviews. No behind-the-scenes looks. No obligatory comments from roadies, fans or management. Everything is stripped down so that the music and the recording of the band take center stage. Even though the cinema audience lacks the direct audience experience of the live concert, this does give you an intimate experience of the band. As a result, a movie theater can turn into a disco with all the seats set aside. The film also does well in open-air cinemas.

The director and Byrne/Harrison duo are restrained in editing. The music is delivered in long takes without quick cuts. Special effects or cutaways to the audience are also avoided. Instead, Demme presents the musicians as if each were a character, developing over the course of the concert. Demme tells the interrelationships of the band members and who is calling the shots and what everyone’s musical part is. It’s wildly clever that your attention is not diverted from the songs. To help viewers know which movie characters they are watching, he films most of the musicians’ shots from six fixed camera positions, one handheld camera and a remote-controlled camera. For the first time ever, the sound is captured digitally on 24-track.

Concert registration of a dance movie? A documentary?

The concert recording can easily be called a dance film with funk music. The remarkable dance moves of frontman David Byrne do not come out of the blue. The choreography has been thought out, as have the dance moves. Everything is rehearsed, just look at the preparation of the eclectic predecessor:

And now for the film. I discuss the concert song by song. You read about the (meaning of the) songs, the presentation and what you see in the film.

Psycho Killer

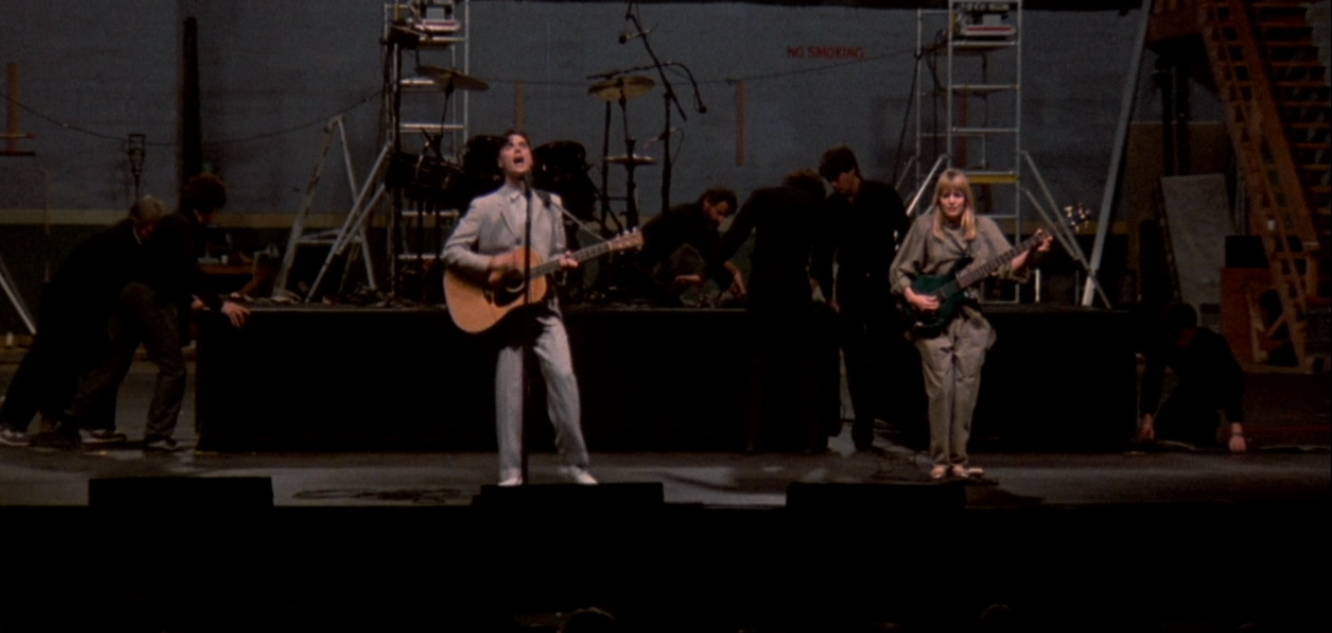

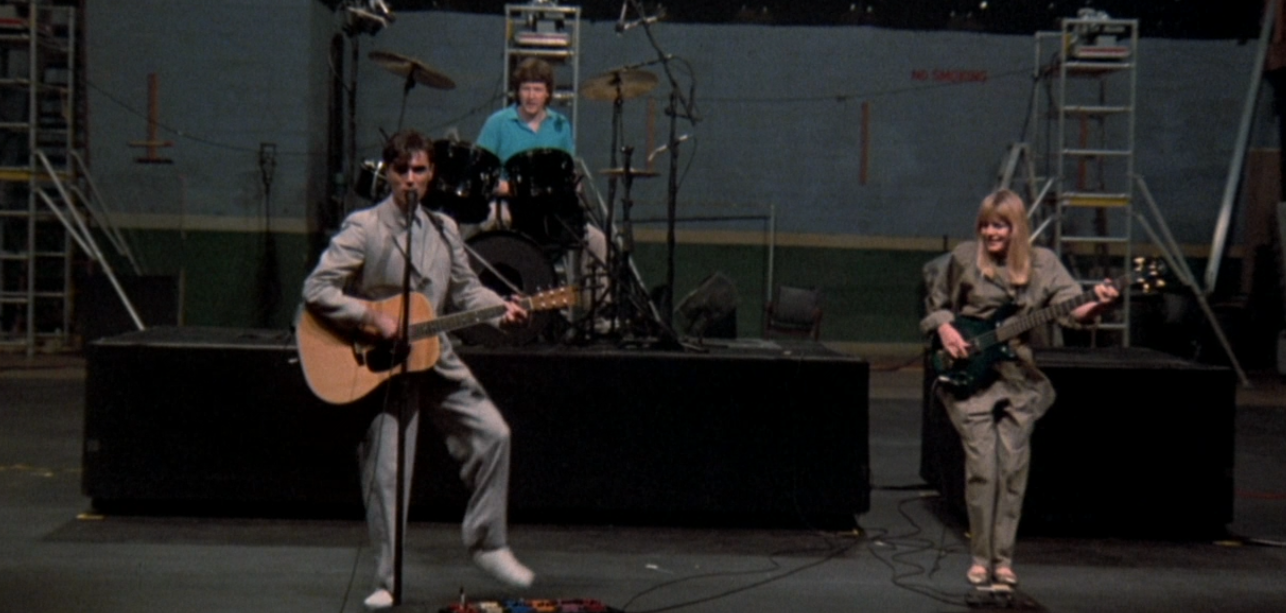

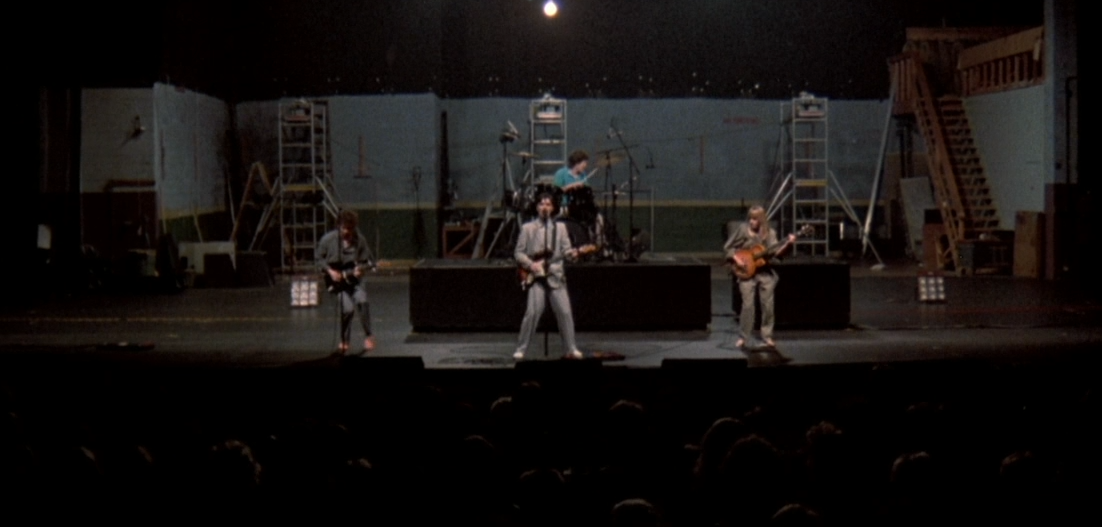

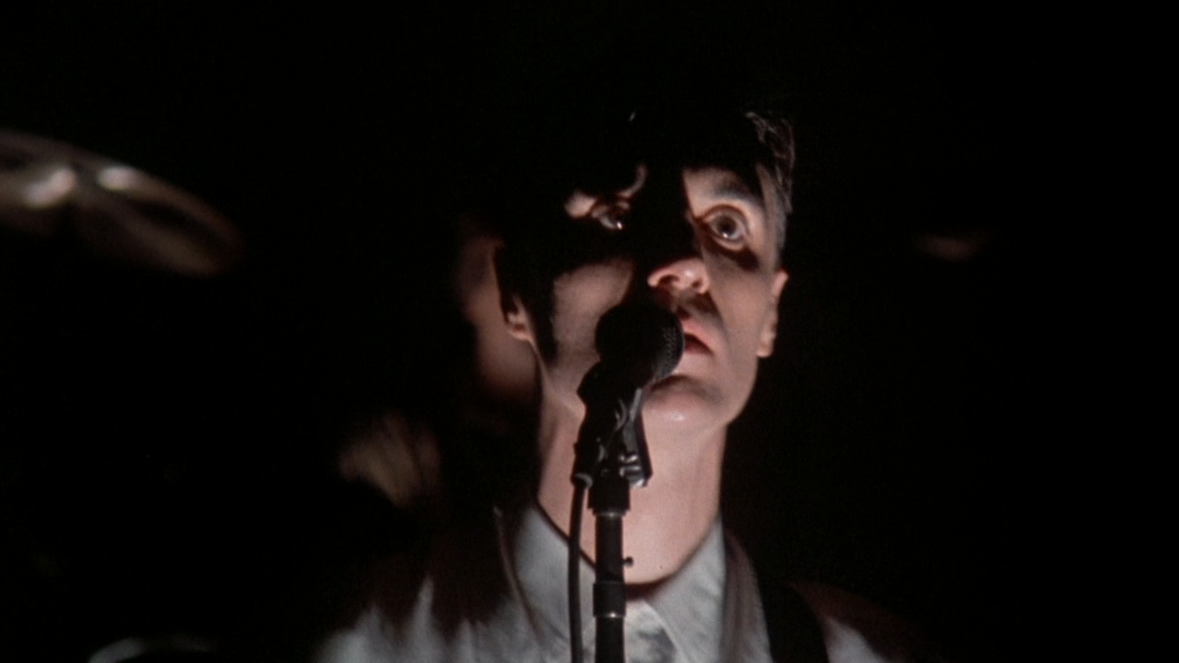

The film begins with a close-up of an empty stage floor. The opening credits are in focus. The camera slowly zooms out. The silhouette of a guitar neck appears and you can hear the sound of spectators swelling. White sneakers walk forward and stop at a microphone. “Hi. I got a tape I wanna play.”

The voice puts down a boombox and turns it on; it produces a mechanical beat. The camera pans up and into view comes David Byrne with a timidly nodding head. Psycho Killer taken from the very first record ’77 is played. You are looking at an empty stage with stanchions against the wall behind the stage. David Byrne looks into the dark; the audience cannot be seen. In the interlude, Byrne gets off balance and stumbles backward on stage in sync with the beatbox. The singer seems to suffer from psychosis, someone who hallucinates and has abandoned reality.

Heaven

Bass player Tina Weymouth – in those days it was exceptional for a woman to play the bass – enters the stage and Heaven is launched. Everyone wants to go to the bar “Heaven,” seeking personal redemption. Heaven, according to the singer, is a place where nothing ever happens, but where fortunately the singer’s music is always playing. Otherwise there would be nothing at all after you die. An invisible female voice, not Weymouth’s, accompanies the singer as if an angel were singing along.

Meanwhile, roadies roll a drum kit onto the stage, behind the singer and bassist in a total shot. While heaven remains sung, the roadies here on earth are busy and don’t bother with anything.

Thank you for sending me an angel

Chris Frantz jumps behind the drum kit and puts in a tight rhythm. The sent angel is thanked and the focus shifts to the drummer. The original lineup from the early days of Talking Heads is now on stage. The emphasis on the rhythm section (bass and drums) will resonate in the music for a long time. The song, however, is not about angels, but about discovering yourself and how to imitate someone’s behavior (“you can talk just like me”), which is quite entertaining for art students who want to avoid conformism instead. It suits the zeitgeist and the age of the band members anno 1978.

Found a job

Fourth band member Jerry Harrison (ex-Modern Lovers) joins. He is often shown in close-up. Harrison has found his new job: guitarist/keyboardist with the Talking Heads. The band is complete!

Total shots can sometimes be seen from the audience, but you don’t see much of the audience. Now synthesizers are rolled in.

Found a job comes from the second album More songs about buildings and food (1978). The three dance across the stage with their guitars in a tight line. In the song, a couple (Bob & Judy) argue about what you’re supposed to do. However, their aversion to commercial TV (“Damn that television, what a bad picture”) keeps them together and they now live happily together. For they have found a new job…. They make, anno 1978, their own TV programs. Did I hear someone say youtubers or TikTok?

Slippery People

The four-piece band is further joined by two singers (Lynn Mabry and Edna Holt) and percussionist Steve Scales. A black cloth sinks down and the scaffolding becomes invisible. Steve Scales sets in with two bongos. The funk is now in the music, just as Slippery People sounds on the Speaking in Tongues album (or even fatter on the 12″ version).

Also special: the vocalists and percussions are of color. In those days, this is very exceptional. Funky songs are still banned from the radio or white MTV. A band consists of white or of black people. “The Lord won’t mind,” the band seems to want to say as a middle finger to the prevailing racism in America at the time. David Byrne dances and the singers dance along and mimic him with air guitars.

Cities

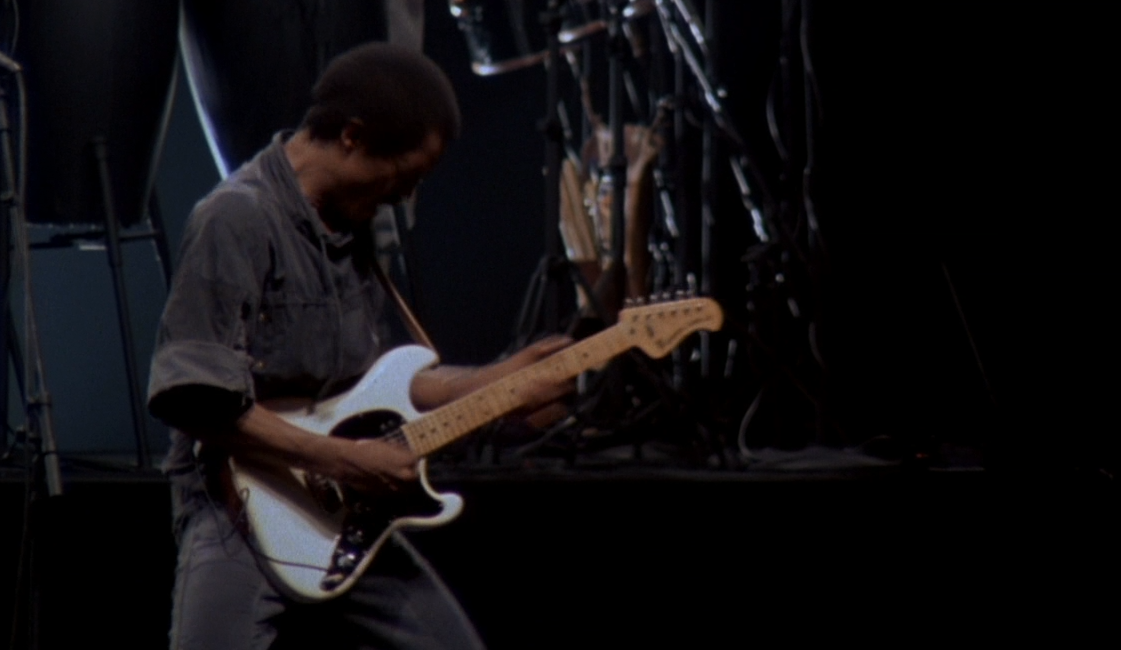

Guitarist Alex Weir (Brothers Johnson) joins the band. In the film, he replaces Adrian Belew (spoiler: things don’t work out on the monkey rock between Byrne and Belew then, which is why Belew doesn’t participate). Weir begins a solo that will have you licking your fingers.

Talking Heads’ third album Fear of Music has song titles playing with mostly just one word. Fear of Music? The band works down a laundry list of everything they’re afraid of. On Cities, David Byrne goes crazy trying to figure out which city he wants to live in. London, Birmingham and Memphis (“Home of Elvis and the ancient greeks”) are all boring and dark. The city is not a good place to live in. The registration is also quiet. The emphasis in the footage is on the drummer and lead singer. There is little opschmuck.

The song is missing from the original 1984 version, but was later made available as an out-take with a reissue on Blu-Ray. You also don’t see Cities in the 2023 4K re-release, but you can hear in on the CD-reissue.

Burning down the house

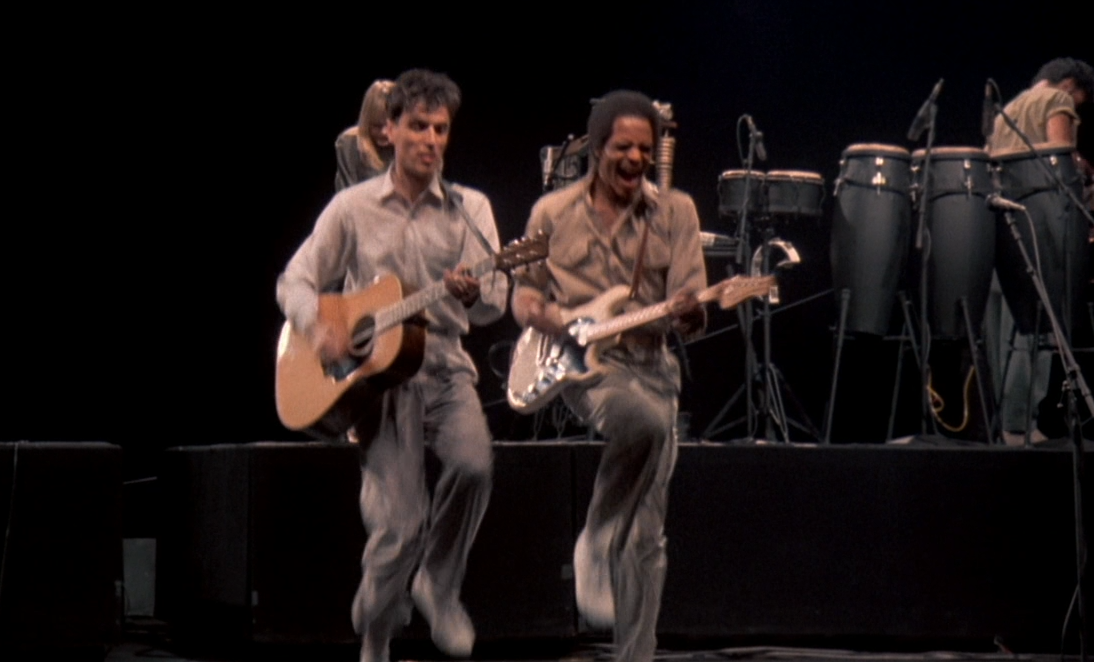

Watch out, Bernie Worrell joins in on keyboards. Byrne and Weir do the same dance moves, as if the guitars were dancing with each other. On the other side of the stage, Jerry Harrison dances with the two singers. Meanwhile, Byrne and Weir seem to be doing a work-out.

And no, Burning down the house is not about arson. The title, David Byrne once told the Wall Street Journal, is a metaphor for destroying something safe that held you captive. You can think of the song as an expression of liberation. You break free from what was holding you back. The lyrics have no hidden meanings.

Life during wartime

The workout that began in the previous song continues. Five musicians run along, sometimes as if imitating Dutch author Theo Thijssens Kees de Jongen’s swimming step. David Byrne, with no guitars at the microphone shakes his shoulders back, as if struck by alien forces during an unclear war. The drum sounds like gunfire being fired.

Byrne makes strange leg and arm movements, seeming to want to fly away like a flamingo. His movements turn into 1950s arm dances. Ain’t got no records to play. The singer, meanwhile, lies on the floor with epileptic jerks, gets back up and runs laps around the stage, out of the war. For Life during wartime outlines a dystopian world with food and energy shortages. And you might be the last one left in an apocalyptic guerrilla war.

‘This aint to party, this ain’t no disco. This ain’t no fooling around.’

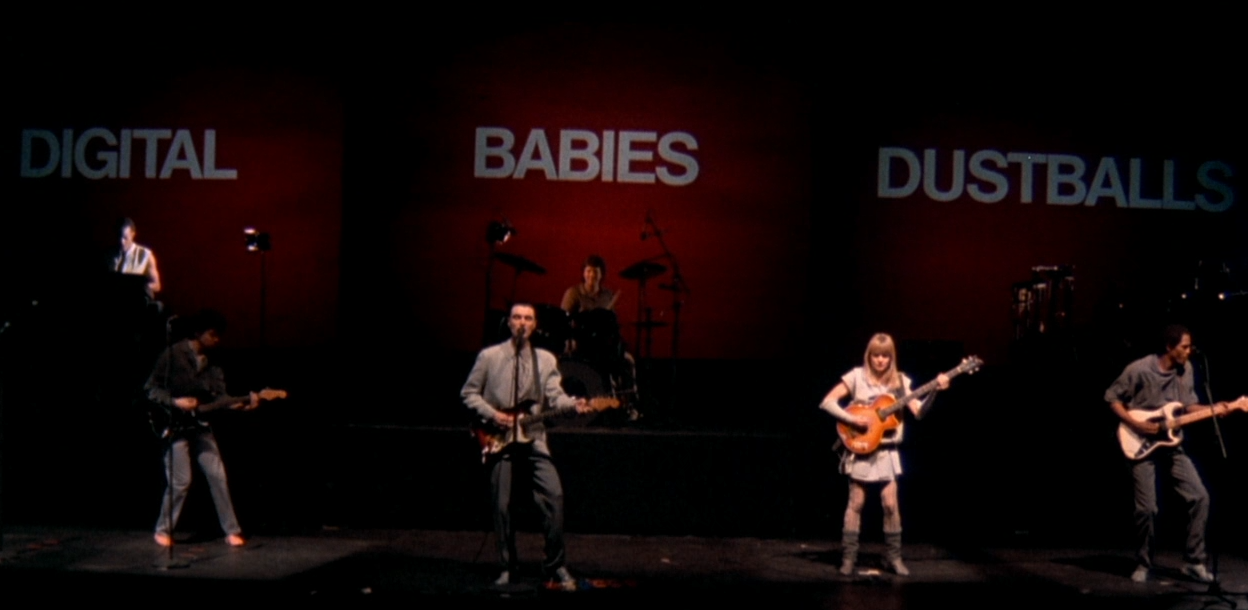

Behind the band, three large projections appear as slides in red. With isolated words like:

DOLL FACE | PUBLIC LIBRARY | ONIONS

AIR CONDITIONED | UNDER THE BED | DRUGS

VIDEO GAME | SANDWICH | DIAMONDS

STAR WARS | FACELIFT | PIG

DIGITAL | BABIES | DUSTBALLS

Making flippy floppy

The song is about the reality of the modern world and how we adults have to go to work every day and live under the government. If you don’t make a “flippy floppy,” you end up in the pit or end up in jail. The main character has his hair tightly combed back in gel. New words appear in the background, in blue:

BEFORE | DINNER | TIME

BEFORE | YOU’RE | AWAKE

LATE | AT | NIGHT

Why these texts? Why the pictures? They attract attention and you can hardly resist interpreting them. No matter how much information you get, not everything becomes clear. Here is the meaning of the film’s title. Stop Making Sense stands for: stop the ratio and let your emotions in. It doesn’t make much sense. Or as the protagonist sings:

Check it out, still don’t make no sense

Making flippy floppy, trying to do my best

Lock the door, we kill the beast (kill it!)

Swamp

The red glow in the background remains visible like burning hell. The devil has a plan, sings the Talking Heads frontman. The musicians can be seen as silhouettes (this element later appears in the music video Love for Sale from the 1986 album True Stories).

Byrne looks into the camera with his stern eyes. He makes spastic movements and drags his leg as if the devil is grazing him. It sounds like the devil wants to destroy the earth. World leaders (at the time: Ronald Reagan) want to stick to patriotism. Meanwhile, the musicians walk a marching pace, seeking a way out of this stifling and complex modern society.

What a day that was

The red from Swamp turns jet black. The exciting song What a day that was is an illustration that this is how we go through life. Some things are under our control, some are not. “We”re going boom, boom, boom. And that’s the way we live.”

What A Day That Was is taken from the David Byrne album The Catherine Wheel. The performance of Twyla Tharp’s dance production can be seen in its entirety on YouTube..

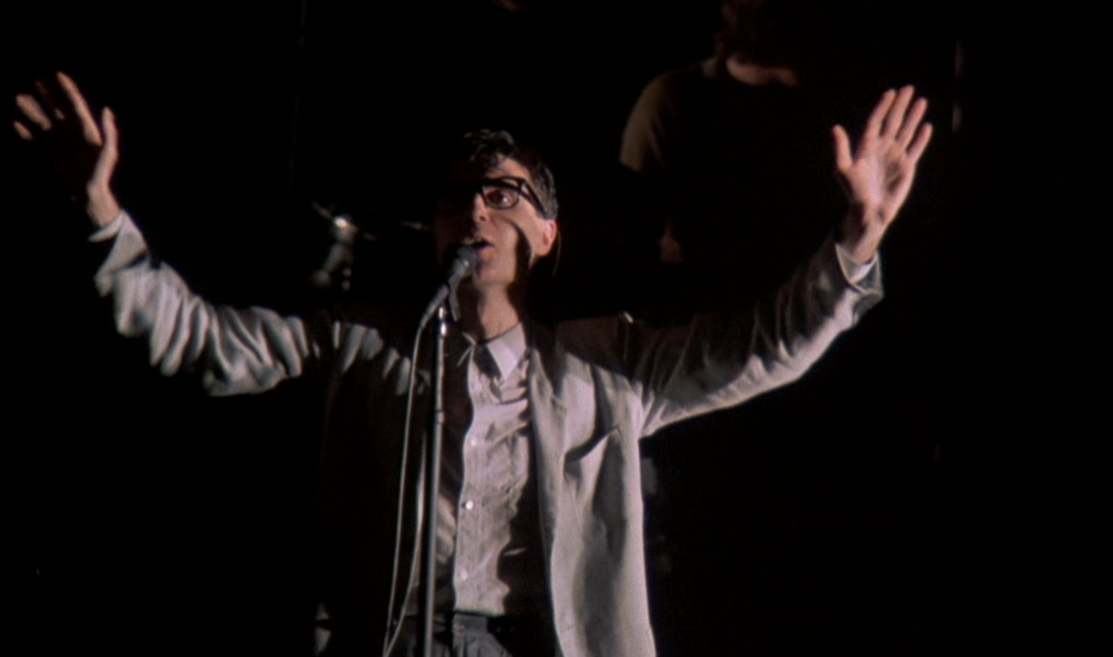

The light is focused on David Byrne’s face from below. He shakes his face violently. This gives a lurid image of the protagonist. The light shines the same way on all the musicians. You can see the little people against the huge shadows in the background and creates a shadow play that makes wajang puppets pale. For the shadow play, David Byrne borrowed from The Catherine Wheel.

Byrne uses the element of shadow play more often in later music videos or concert films, most recently in the song Blind in the American Utopia-tour (2019). The singers sing loud and long full of uncertainty.

And on the first day, we had everything all in hand

Oh and then we let it fall.

This must be the place (Naive melody)

In the film, the set is completely transformed into a traditional living room. David Byrne dances like Fred Astaire, but with a floor lamp. He embraces the lamp and dances with it with movements like a chicken. The protagonist is simply looking for a home of his own, a place under the sun. Life is so fleeting, it might as well last a minute or two. When you realize how short and fleeting life can be, you might as well embrace the mundane, like a floor lamp, and stay together.

In the background appear new slides of arms, hands, bellies, buttocks and knees and domestic armchairs (in real life they are Byrne’s photographic artworks, once on display (and for sale) during the solo exhibition “Photo-works” at the Leiden art gallery Stelling Gallery in 1994).

On the Speaking in Tongues album, most of the musicians play a different instrument (hence the subtitle ‘Naive Melody‘).

Once in a lifetime

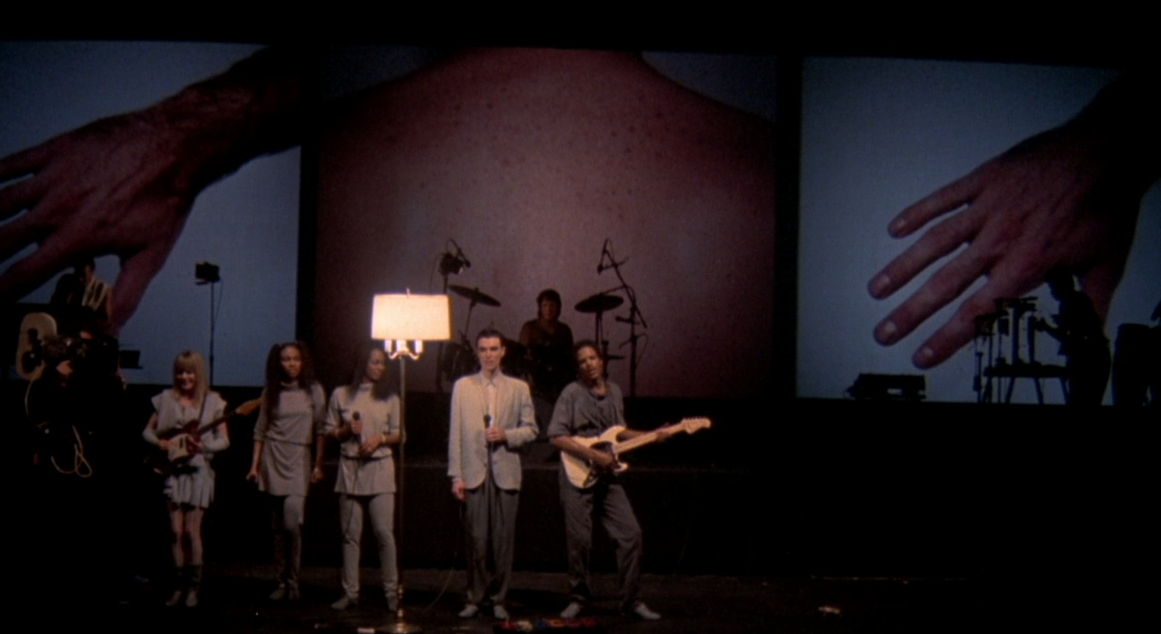

Once in a lifetime is in the history books and will certainly end up in an I.M. by David Byrne at some point. I hate to say. It is the band’s signature hit, taken from Remain in Light (1980). Where in This must be the place the protagonist has found his home, this is about the transience of life. The song is a sample of sermons by American evangelical pastors that Byrne recorded from the radio.

The protagonist wears dark glasses and sings with widely spread arms high in the air as if he is ecstatic. Ok, then you live in a nice house, with a beautiful wife and a big car out front, and then you think: what’s in it for me? The days go by, life goes on and life changes and returns to how it was. Same as it ever was. Yet Once in a lifetime encourages you to keep going, even if life is different than you expected. Make the most of it.

Byrne does dance moves with his hands that come from the Nigerian natural Yoruba religion. You can see those here.

The dance moves in the film were also copied from Japanese teenagers. “I worked at a hot dog stand, New York System, where you put the hot dogs around your arm like that. But I got that thing from, I saw those Japanese kids dancing in the park in Tokyo, those kind of rockabilly dancers, and then there were those kind of space cadet kids who had a completely different set of moves. I videotaped some of them and that’s where I got that from.” (source: Stereogum).

Big Business / I Zimbra

We return to The Catherine Wheel. The number of references to the dance production is there for a reason. Big Business is from the music score by David Byrne, only. It is the time when the band members each went their separate ways. Chris Frantz and Tina Weymouth released albums with the Tom Tom Club (including the widely known Wordy Rappinghood, Genius of Love and a cover of Under the Boardwalk) and Jerry Harrison came out with the more intelligent The Red and The Black, both from 1981.

Flanking artists such as Adrian Belew, Brian Eno, Steve Scales helped the side-projects. Adrian Belew and Bernie Worrell play on The Tom Tom Club, The Red and The Black and The Catherine Wheel. Steve Scales sticks to The Catherine Wheel, which also features Jerry Harrison.

Think you’ve had enough

Stop talking, help us get ready

Think you’ve had enough

Big business after the shakeup

Think you’ve had enough

Stop talking, help us get ready

And you think you’ve had enough

Big business after the shakeup

Get ready get ready

Stop talking, help us get ready

Stop

Big business flows smoothly into I Zimbra, the dada poem by the Swiss artist Hugo Ball. The art students are indebted to Ball. I Zimbra is the opener of Fear of Music and showcases the first huge influences of African music and shows where the band is going: My life in the bush of ghosts from 1981 – but recorded earlier than – Remain in Light (1980) are born into I Zimbra.

Unfortunately, the double track cannot be seen in the 4K version, as it fumes and pumps and steams. You can, however, see it as outtakes on the Blu-Ray Disc ( or here on YouTube ). It can also be heard on the 2023 CD re-release.

Genius of Love (Tom Tom Club)

Time for couple Chris Frantz and Tina Weymouth’s oafish side-project Tom Tom Club. In Genius of Love, it becomes clear how the band is growing apart. Byrne experiments with performance theater, samples and intricate polyrhythms (My life in the bush of ghosts, The Catherine Wheel) and Tom Tom Club goes on the reggae tour from their studio in the Bahamas. With a fine love song, it seems. Or is it more about drugs after all (What you gonna do when you get out of jail? We went insane when we took cocaine).

Byrne is off stage for a while. Why? Soon after this song it becomes apparent.

Girlfriend is better

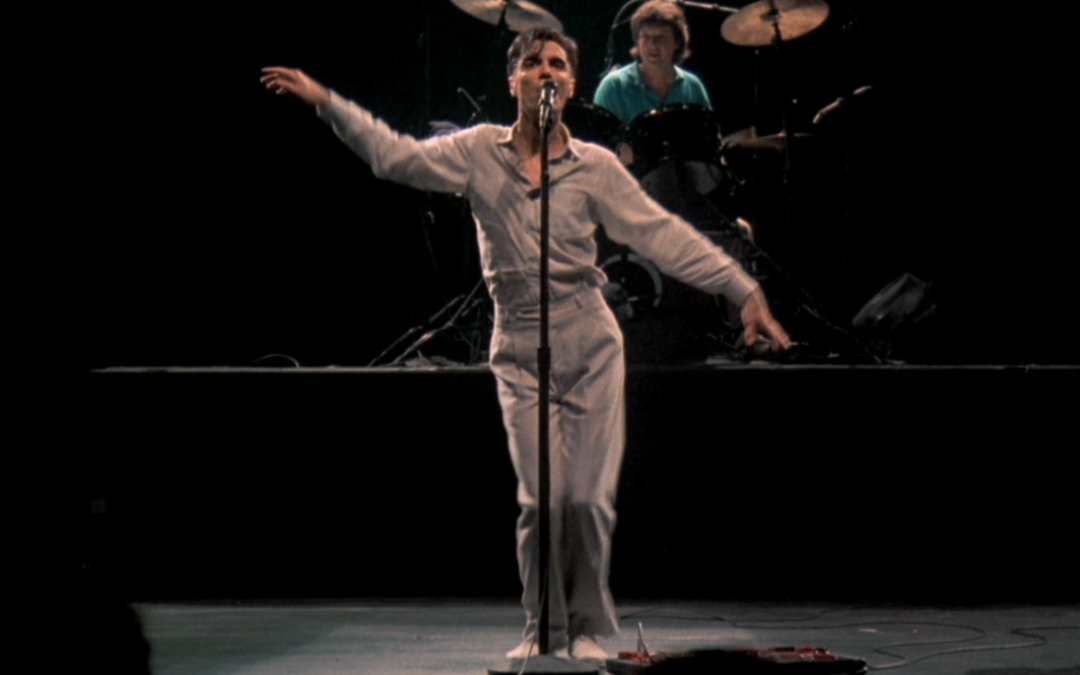

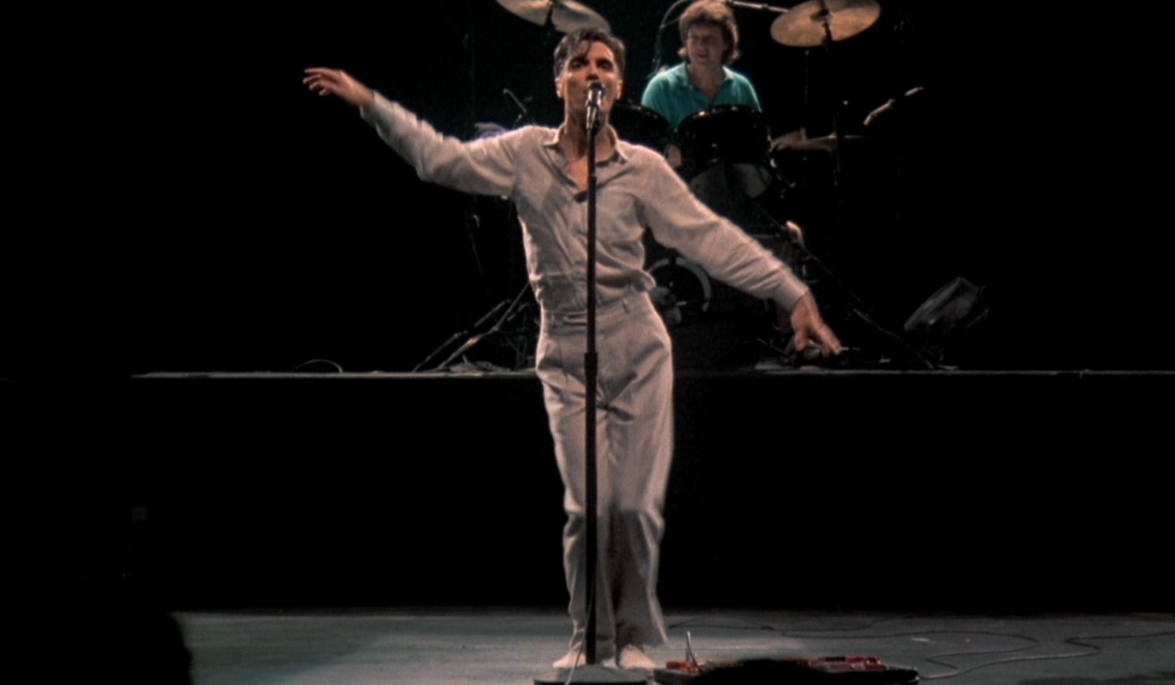

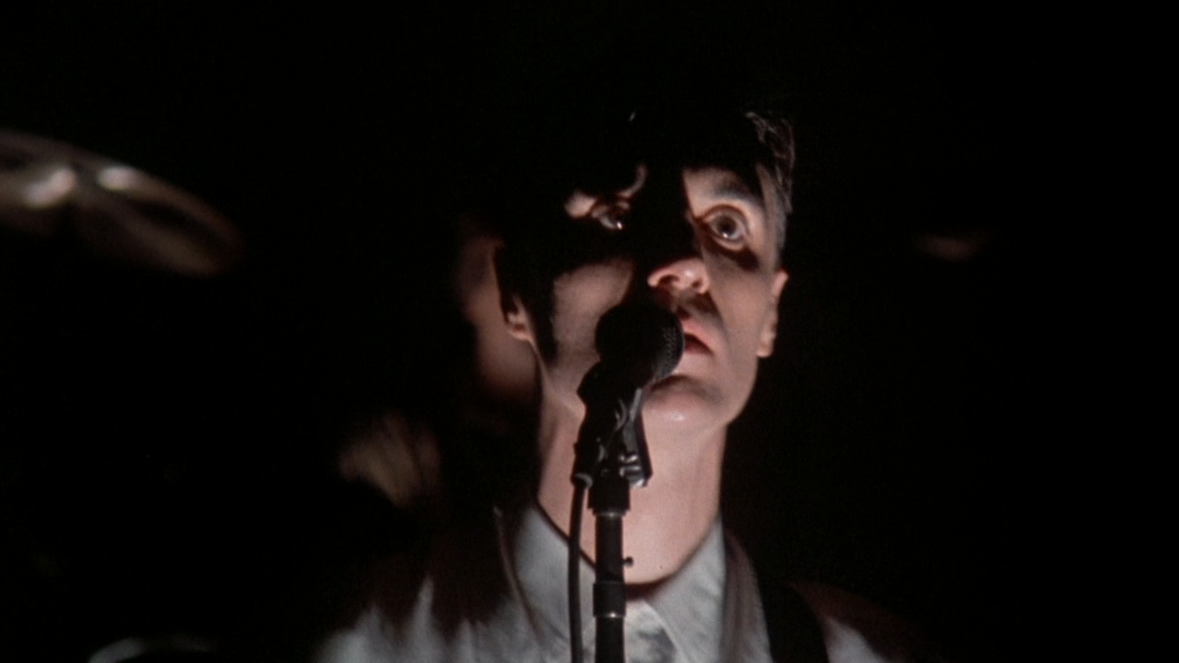

To further accentuate the removal in the band, it is now the turn of Girlfriend is better, also from Speaking in Tongues. On screen is the silhouette of a broad-shouldered singer wearing the legendary big suit.

When the band visited Japan, David Byrne looked at traditional theatrical forms such as Kabuki, Noh and Benraku. “Everyone wore giant intricate costumes and moved in unnatural ways. Was any of this applicable to a performance of pop music? I didn’t know, but every other night at dinner in Tokyo, the fashion designer Lee came up with the old adage that ‘everything on stage should be bigger.’ Inspired by this, I sketched out an idea for a stage outfit: a suit, but bigger and styled like a Noh costume. That wasn’t really what he meant. He was talking about gestures, expression, the voice. But I also applied it to clothing,” he says of it in How Music Works.

Byrne’s big suite is a landmark in film history.

The scrawny little guy has become a big guest with slovenly dance moves. In the background, the shadow play is back. The first song line (‘Who took the money?’) shows the protagonist arguing about money like a rock-hard businessman. You don’t get a grip on what exactly is going on,. That’s often the case with Talking Heads’ songs. Until at the end of the song Ednah Holt and Lynn Mabry sing with David Byrne

As we get older and stop making sense / You won’t find her waiting long / Stop making sense, stop making sense / Stop making sense, making sense (Hahahaha) / I got a girlfriend that’s better than that / And nothing is better than this / Oh, is it?

The Big Suit (links) en een Noh-kostuum uit de 18e eeuw.

Take me to the river

What follows is the cover of Al Green’s Take me to the river about a man in love with an underage girl. When gospel and soul singer Al Green was 28, he was in a relationship with a 16-year-old girl. She commits suicide because she cannot get married. In the sequel, Green seeks redemption and gospel rings loud in the song. A double meaning is in the title: The girl goes to the river to commit suicide (“Love me til I can’t take no more. Take me to the river“). Byrne takes off his big suit at that point.

Later in the song, the character goes to the river to cleanse himself of all the suffering. ‘Take me to the river. Wash me in the water. Feeling good‘.

Steve Scales takes the floor and encourages band member Jerry Harrsion and the audience, hitting his rhythm with a cowbell. David Byrne introduces all the band members. All the musicians are dressed in light gray or dark green (at the beginning, Chris Frantz can still be seen wearing a different light blue t-shirt, mistake?). Byrne wears a striking red cap. The music steams and steams through the room like a steam train. The lights come on and for the first time we see dancing audience. Byrne leaves the stage. The film is finished, it seems.

Crosseyed and painless

Of course not. No concert without an encore.

All of Talking Heads’ lyrics are duplicitous, paranoid or contradictory. That having said, the concert ends with Crosseyed & painless. Do you stay the same, or do you change direction in your life? Do you rely on facts, or not what they distort the truth, are never what they seem. It seemed so clear, but you are stranded on an island of doubt. Perhaps redemption lies in deconstructing to better understand the world. Just as Stop Making Sense is a deconstruction to construct a film: from an empty stage to a steaming concert hall with nine jumping musicians going wild. The concert ends with screaming guitar solos by Alex Weir.

And then still in the picture: the audience and crew coming onstage. Good night.

Does anyone have any questions?